Breaking the Silence

Menopause is often spoken about in hushed terms. But physiologists are advancing our understanding of this natural life shift.

By Jennifer L.W. Fink

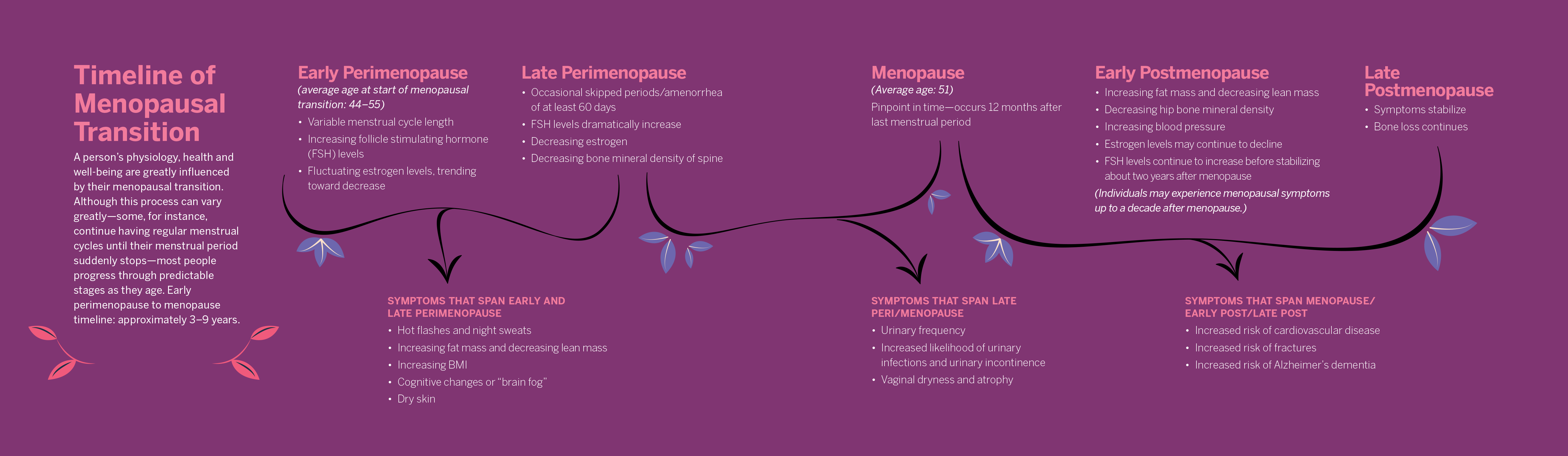

Anyone with ovaries who lives long enough will eventually experience a decrease in production of estrogen. Menstrual cycles will cease, and their physiology will change, as the body no longer produces regular, predictable quantities of hormones that affect the functioning of nearly every organ system.

Some people will have a tough time falling or staying asleep. They may struggle with “brain fog” and feel frustration because once simple cognitive tasks require extra effort. Occasional bursts of internal heat may trigger sweating and discomfort. Urinary dysfunction may occur, sexual functioning is affected, and a person’s risk of osteoporosis, bone fractures, heart disease, high blood pressure and Alzheimer’s dementia increases significantly.

Yet, even though menopause is a universal experience for half of the human population, scientists and clinicians still understand little about the physiological process of it.

“We don’t really know the underlying biological changes that are occurring as women are going through menopause,” says Kerrie Moreau, PhD, professor of medicine in the Geriatrics Division at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Scientists don’t know precisely what causes hot flashes, a vasomotor symptom that affects as many as 75% of North American women as they go through the menopausal transition. And very little is known about women’s metabolism after menopause, says Virginia Miller, PhD, FAPS, professor emerita and former director of the Women’s Health Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Although massive gaps in knowledge remain, scientific understanding of menopause has increased greatly over the past 20 years or so, largely due to the work of resolute physiologists.

“We now have more women in science, and many of us want to study the female physiology and diseases that impact us directly and may have been ignored in the past,” says Heddwen Brooks, PhD, professor chair of the Department of Physiology at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans. “This is why having more diverse scientists is really important. We women spend a third of our lives in menopause, if we are lucky, and understanding how menopause changes our physiology is important.”

Flawed Studies Hinder Research

Scientists and clinicians have long known that the risk of heart disease, osteoporosis and some cancers increases after menopause. So, in 1991, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute launched the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) to better understand how diet, hormone therapy (HT), and calcium and vitamin D supplementation impacted the health of postmenopausal women. These studies were not intended to elucidate the physiology of menopause or to outline the typical progression of the menopausal transition. Rather, the intent was to determine the effectiveness of possible treatments for health conditions that commonly affect older women.

“After the Women’s Health Initiative was halted, “we had to temporarily suspend research … and [it became] a recruiting nightmare to try to get women into [our] study.”

Kerrie Moreau, PhD

However, the WHI was stopped abruptly in 2002 after researchers noted a statistical increase in breast cancer and stroke—and no apparent benefit for reducing cardiovascular risk—among women taking HT. HT prescriptions and usage plummeted, and science was stifled.

“We had to temporarily suspend research,” says Moreau, who was studying the effect of different types of hormone therapy alone and combined with aerobic exercise training on vascular aging at the time. The National Institutes of Health required her (and other researchers) to inform all potential research subjects of the increased risk of cardiovascular disease with hormone therapy, and it became “a recruiting nightmare to try to get women into the study,” she says.

Reanalysis of the WHI data revealed several flaws: The study combined women from a large age range, 50 to 75, so it included women well past menopause. Many women in the study received HT for the first time a decade or so after their last menstrual period—a choice that didn’t reflect clinical practice at the time. Plus, previous observational studies had noted reduced coronary artery disease among women who took hormones at the time of menopause.

The WHI study used orally administered conjugated equine estrogen—which contains some estrogen but is mostly estrogen metabolites such as estrone sulfate—in combination with a synthetic progestin. This was different from the natural hormone 17β estradiol, which is what’s used in laboratory settings and can be delivered transdermally. The transdermal approach is closer to how bodies naturally get estrogen.

The much-publicized increase in breast cancer risk didn’t apply across the board, and an updated analysis of the breast cancer findings of the WHI Estrogen-Alone Trial found that estrogen-alone HT does not increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. (That analysis was published in the April 12, 2006, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.)

When the data from the WHI study were stratified by age, those women who were given estrogen early in menopause saw some protective effects. The incidence of diabetes was reduced, Brooks says, and no detrimental impact was seen on the cardiovascular system.

Nevertheless, after 2002, there was a sharp decline in menopause-related studies. To this day, many women are hesitant to take hormones to relieve menopausal symptoms and many clinicians are reluctant to prescribe HT to postmenopausal women, even though HT is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat symptoms and prevent bone loss after menopause.

“It has become a problem for many women to find a physician who will prescribe them [hormone replacement therapy] as many have not kept up to date on the science following the initial release of the WHI data,” says Brooks, who’s been studying the molecular signaling pathways involved in postmenopausal hypertension for decades. “We need to educate women and physicians to consider that not all HT is the same. The route of delivery—oral versus transdermally—matters.”

Menopause Is More Than Estrogen Loss

Because estrogen levels decrease dramatically as women go through menopause—with women in their 60s having lower estrogen levels than men of the same age—much research has focused on understanding estrogen’s impact on the cardiovascular and other organ systems.

Miller has examined the vascular function of estrogen, showing that estrogen affects vascular responsiveness and enhances production of nitric oxide in the vascular endothelium. It also affects regulation of intracellular calcium. These functions may explain, at least in part, women’s increased risk of cardiovascular disease after menopause. Other effects of estrogen include modulation of beta-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle and regulation of the renin angiotensin system, all of which contribute to an increased risk for hypertension, stroke and heart attack.

“We’re just beginning to understand that there are sex differences in the way sex steroids work to control blood pressure,” says Jane F. Reckelhoff, PhD, FAPS, professor of pharmacology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and APS past president. Large studies have shown that women’s blood pressure, pre-menopause, is generally lower than men’s. However, between the ages of 40 and 60, when most women are undergoing the menopausal transition, there’s a significant increase in women’s blood pressure, and after age 75, women are more likely to be hypertensive than men, Reckelhoff says.

Researchers have learned, via animal studies, that boosting estrogen levels does not decrease blood pressure. “There’s a point where animals stop responding after a certain age,” Reckelhoff says, which may be why some human studies have found that estrogen replacement does not lower blood pressure or reduce risk of hypertension in women. Reckelhoff suspects there may be “some change that occurs with aging to the estrogen receptors, so that the response to estrogen isn’t the same as it was prior to menopause.”

Research by Brooks and others suggests increased T cell-mediated inflammation during postmenopausal hypertension. Pre-menopause, females have more regulatory T cells than males, but females’ T-regulatory cell populations decrease during the menopausal transition. “We’re trying to understand, if we restore regulatory T cells, can we protect cardiovascular disease?” Brooks says. “We have data to show that we can.”

Increased systemic inflammation may play a role in the development of menopause-associated asthma, an under-recognized sub-type of asthma that is physiologically different than asthma in children or adult males. While researchers are still working to understand the biologic mechanisms at play, they’ve learned that menopausal status, not age, increases the risk of new-onset asthma.

Additional research into the immunologic impact of menopause may point the way to new treatments. Although immunotherapy is now commonly used to treat cancers and some autoimmune diseases, “people don’t think about immunotherapy for cardiovascular disease. But I think it’s quite feasible, perhaps in the next 20 years,” Brooks says.

Although nearly 1 in 3 women said menopause symptoms interfered with daily life, only 44% discussed potential treatments with their health care providers.

An increased understanding of the role of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) during the menopausal transition may also lead to new therapeutics. Although scientists and clinicians once thought that estrogen deficiency caused dyslipidemia in menopausal women, high FSH levels are more closely correlated with total and LDL cholesterol postmenopause.

Increased FSH levels also appear to trigger increased adiposity, abdominal weight gain and bone loss and may negatively affect cognitive function. One study noted an association between elevated FSH levels and a reduction in bilateral subcortical volume of the amygdala; other studies showed neurofibrillary tangles and impaired cognitive activity as FSH levels increased in ovariectomized mice. A 2022 in vivo study showed that administering an FSH-blocking antibody reduces tangle formation in the brains of mice and improves cognitive function. Other mouse studies have found that blocking FSH reduces body fat, lowers serum cholesterol and increases bone mass.

Moreau and colleagues are actively working to learn more about the role of FSH in postmenopausal changes in body composition and vascular function. “We’re giving postmenopausal women GnRH antagonists to lower FSH levels. Then we’ll see if there are changes in adiposity and vascular function,” she says. “We’ll have a group that also gets estrogen, so we can look at these different paradigms and try to pinpoint what’s more important, estrogen or FSH. It may turn out that both are playing a role.”

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore have developed a first-in-class FSH-blocking antibody that has been shown to prevent and treat osteoporosis in mice. They hope it may one day be used to prevent and treat human obesity, osteoporosis, dyslipidemia and neurodegeneration.

Shifting Menopause Management

Although scientific understanding of menopause has advanced, clinical management of menopause-related symptoms and health conditions hasn’t shifted much. At present, most females do not receive treatment for troublesome menopause symptoms. Although nearly 1 in 3 women said their symptoms interfered with daily life, only 44% discussed potential treatments with their health care providers, according to the 2022 National Poll on Healthy Aging.

The American Medical Association recommends an individualized approach to menopause management, with HT used to alleviate bothersome symptoms. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says that “menopausal hormone therapy should not be used for the primary or secondary prevention of coronary heart disease at the present time,” while supporting the use of HT for relief of menopausal symptoms in women who are in early menopause and good cardiovascular health.

By studying the physiologic changes related to menopause, researchers are paving the way for more targeted treatments that may ultimately improve the health and quality of life of women worldwide.

This article was originally published in the November 2023 issue of The Physiologist Magazine.

“We now have more women in science, and many of us want to study the female physiology and diseases that impact us directly and may have been ignored in the past.”

Heddwen Brooks, PhD

The Physiologist Magazine

Read the Latest Issue

Don’t miss out on the latest topics in science and research.

View the Issue Archive

Catch up on all the issues of The Physiologist Magazine.

Contact Us

For questions, comments or to share your story ideas, email us or call 301.634.7314.